Cinematic Anamorphic Video

Just this past week, I picked up a used anamorphic lens adapter. This adapter allows me to convert a useful selection of my lenses to be used to create cinematic wide screen videos with most of the characteristics of far more expensive cine lenses.

True cine lenses are both huge in size and exhorbitantly expensive when compared to typical camera lenses used for still photography. These anamorphic lenses are used mostly by filmmakers because this type of lens is actually designed to fit wide-screen cinematic video on smaller film and digital sensors.

Back in the 1950s, movie studios were filming on 35mm film. Some studios were probably still using 16mm film too but major productions were using 35mm film. By comparison, home movies were being filmed on 8mm film. I was very well versed on 8mm film through the 1960s and 1970s as that is the format my family used for all our home movies.

By the time I was in high school in the mid-1970s, I was cutting and splicing 8mm film to create longer home movies. The typical roll of 8mm film only recorded about two minutes of video which fit on a very small reel. I would cut out bad spots of the movies... ie, out of focus, too shaky, too over-exposed due to light leaks.. and then splice together longer home movies on much larger reels that held about 20-30 minutes of video.

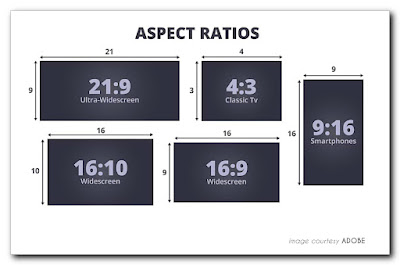

These early 8mm films were in a 4:3 aspect ratio. Much more expensive, larger and more professional grade 16mm film was also in this 4:3 aspect ratio. Even the ridiculously expensive film that the larger production studios used was 35mm film in a ratio of 3:2 which isn't much wider than the 4:3 aspect ratio... ie, 8:6 vs 9:6... but it was wider nevertheless.

In the 1950s, movie studios and theatres were having trouble filling the seats at theatres across the country. In an effort to put paying butts in the seats in the theatres, the production studios found a way to squeeze a much wider format onto this film that was meant to record only 4:3 or 3:2 movies. Out of economic necessity, this is when anamorphic lenses were beginning to become more mainstream by filmmakers.

At the time, the film needed to remain the same in order to keep costs down. If they changed the film to an even larger format, then the film would cost more. As it was, 35mm movie film was very expensive per foot. If I remember correctly, roughly speaking, a 1000' roll of 35mm movie film only played about 11-15 minutes of video. And the cost of the film was high, the cost of developing the film was high, and the cost of the projectors in movie theatres was high.

Moving to larger film wasn't something the production studios wanted to do because it would require a huge investment in resources, training, education, time and newly designed equipment. Additionally, if the production studios changed the film, then every theatre would need to purchase new equipment to handle the larger film. Higher costs for the theatres would create an insurmountable issue for the struggling movie theatres especially at a time when movie theatres were less popular.

The filmmakers (well... the tech guys, really) came up with a plan to squeeze wider views onto the existing commercially available film by using anamorphic lenses. The lens would squeeze the horizontal view so that the wider view would still fit on existing film whether it be 8mm film, 16mm film or 35mm film. The only thing the movie theatres would need to do is enlarge their screens which is really a minimal cost especially if this change promises to fill the seats again.

The next thing to address is the common misconception that the top and bottom parts of the wide screen cinematic image are cut out to create this wide screen cinematic format. Absolutely not. This is completely wrong. We start with a recording in the 16:9 format (see image above) which is the natural position and shape of the digital sensor (or film but film wasn't as wide naturally, hence the need for the first anamorphic lenses) and then we're stretching the image horizontally until it is stretched to the 21:9 wide screen cinematic format. No part of the image is cut.

If a person has two eyes on their face, side-by-side, then seeing wide is a very natural thing. If those eyes were one on top of the other, then seeing in a vertical aspect ratio would be the natural thing. There are two points here. First, contrary to popular misconception, no part of the image was cut to make this wide screen cinematic format and, second, seeing w-i-d-e is natural for people with eyes that are side-by-side. It seems that people who see black bars on their television screen on top and at the bottom of the image erroneously conclude that those black areas were cut. No... the real reason you are seeing black bars at the top and bottom of your screen is because your television screen isn't wide enough. It has absolutely nothing to do with the top and bottom of the image. If your television screen was wider, then the whole image could be enlarged wider and taller to fit your screen perfectly.

Now, when you see black areas all around the whole image on your television, that is a whole different problem. That means that your television screen has far more pixels than the video you are watching. A low resolution video may only be 1024 pixels (or 1280 pixels) by 720 pixels high (or even smaller) while your television displays 1920 by 1080 pixels (HD television) or 3840 by 2160 pixels if a 4K television. So, if you play an old standard definition video on a HD or 4K television, you'll likely see blackness around the whole image because the image is far smaller than what the television provides in pixels. Of course, television manufacturers also provide a way to "fill the screen" in this case by changing the television's display parameters but most people have no clue how to do that with a simple button push on their remotes. And, some televisions are better at this due to high quality upscaling while other televisions (ie, cheap televisions) will only show a pixelated enlarged view.

So, anamorphic lenses became more popular for filmmaking starting in the 1950s into the 1960s in order to fit a wide screen cinematic view onto a narrower and smaller film frame. These anamorphic lenses also had very unique characteristics that audiences found appealing.

These lenses rendered a very organic view. The out-of-focus areas of the view had a tonal density that was (and still is) rather appealing. (Pay attention to the out-of-focus areas of my video clips below.) Bright lights in the frame caused a unique streaking and lens flares (also in my video below). This streaking (usually in a blue hue but sometimes white or gold) would become very appealing and synonymous with film. These lenses would also create orb-like lens flares that would line up with the light source. Additionally, because of the horizontal squeezing and then de-squeezing of the image, there was a surprisingly forgiving less-than-razor-sharp image. This less sharp image also provided a more organic tonal quality across the frame.

So, the anamorphic lens has been the preferred lens for filmmakers for decades.

An amateur filmmaker (think Indie filmmaker) could easily spend between $25,000 and $50,000 for a limited set of about three or four lenses. Production studios easily spend five to six figures per lens. Each lens has its own focal length and field of view so multiple lenses are always needed for different views. Duplicate lenses are needed for multiple cameras showing different angles. In short, professional filmmaking is expensive and the anamorphic lens is one of the filmmaker's tools.

For someone like me who is just an enthusiast like my father as well as my grandfather (both who taught me a great deal about this artistic hobby), you can still get a taste of filmmaking at a far lower cost. Of course, the lower cost comes with significant compromises.

As one would expect at this price point that I paid, these adapter lenses also often have multiple optical deficiencies that better anamorphic lenses will not exhibit. For someone like me who is only an enthusiast rather than a professional, however, these adapter lenses can be exciting to use and allow us to create views we wouldn't be able to create otherwise while giving us a taste of what a true anamorphic lens can create. In my case, I purchased this used anamorphic adapter lens for about $300 (I rarely buy anything new)

Most of today's cameras shoot video in a 16:9 aspect ratio. While this is still much wider than the older 4:3 and 3:2 aspect ratios of film, it is still not at cinematic wide screen widths. For this, we need to stretch to 21:9 or even wider. My new adapter lens records horizontally squeezed video onto my camera's native 16:9 camera sensor and then I can de-squeeze it to a 21:9 aspect ratio in post-production for a much wider field of view.

The above photo of filmmaking aspect ratios from Adobe also shows a 9:16 vertical aspect ratio but, in my experienced opinion spanning decades of photography and filmmaking on film as well as digital sensors, this tall, narrow format used by far too many of today's "content creators" and "influencers" is absolutely absurd. I suppose that if the human had eyes placed one on top of the other rather than side-by-side, then the 9:16 format might make more sense. Since we do really see wide with eyes that are placed side-by-side, wide screens are a natural fit.

Viewing videos in this 9:16 vertical aspect ratio is like trying to peer through two fence boards like a peeping Tom with only one eye because the boards are so close together! Turn your damn phone to its horizontal position and record video as your eyes see the world!

Recording video in the 9:16 aspect ratio is simply idiocy or maybe laziness. I can get into a very long explanation of appealing composition and what the eye naturally follows but that is another topic for another day. Just know that I find this vertical video format to be insane idiocy lacking creativity, artistry and common sense.

So far, I've tested this anamorphic adapter lens on a camera body with an APS-C sensor and another camera body with a slightly smaller four-thirds sensor. I plan to test it on a camera body with a full frame 35mm sensor but haven't gotten to that camera body yet. I tried lenses with focal lengths ranging from a very wide 16mm to a standard 55mm. I have to say that the two extremes did not work well enough for me. Truthfully, they didn't work at all for various reasons. That being said, using lenses with focal lengths in the 24mm to 35mm range seems to work well enough and, in some cases, very well. The clips in the video below were shot in this range.

This adapter lens, although not nearly as large as a dedicated anamorphic lens, is still large enough that it makes handholding the camera difficult (82mm front element). I have my rig mounted on a video support rack that supports this big adapter lens rather than letting the weight of this big adapter pull down and add stress on my lens mount. Needless to say, this adapter lens really only works well on a tripod. Of course, if I had a true giant-sized anamorphic lens, hand-holding my camera would also be out of the question.

Here is a short video showing a couple of the characteristics of anamorphic lenses. This video also contains a few sample video clips.

Great stuff!

ReplyDelete